When is commitment bad?

Identifying with your profession or team leads to being committed to it. This identity influences your behavior and values. Too much of it, and you will be blind to shortcomings.

You are working for a small company. Everyone has their main priority and does things outside their area of expertise. During a meeting, everyone wants to outsource or automate customer support. This is your domain: you know the risk of being less active in this part of the business, but no one is really paying attention to your concerns.

What do you do? Do you align with your team or put your foot down and disagree?

In the scenario, two forces are pitted against each other: Commitment to your team and commitment to your profession. Someone committed to the team would give in and accept the team's decision. The consequence of this is team cohesion, something you want (of course, up to a certain degree). Someone committed to their profession would disagree with the opinion of team members and push for their professional expertise to be heard and recognized. The consequence of this is continued conflict between team members.

Of course, this is a simplification of life.

Commitment to your profession or team doesn’t originate from anywhere. It derives from your social identity. Social identity is the idea that people want to belong to specific groups, and that this group membership influences their behavior and values.

a commitment to your personal mission?

— Anna Grigoryan (@angrigoryan__) February 4, 2022

Framework: Social Identity

Social psychologists Henry Tajfel and John Turner developed social identity theory in the 1970s. They were trying to understand social processes such as discrimination, aggression, and conflict between different social groups: Catholics vs. Protestants, Bootstrapped funders vs. VC-funded funders, managers vs. individual contributors).

Social identity theory claims that people want to be part of a social group because it simultaneously gives them a feeling of belonging and uniqueness. The sense of belonging is satisfied thanks to being a group member. At the same time, the feeling of uniqueness is taken care of by not being a member of other groups. In other words, you are not alone as you belong to a group, but you are also not a robot because you are different from those people who are not part of your social group.

Social identity theory does not argue that we want to be exactly like everyone in the group. Marilynn Brewer, now visiting professor at New South Wales University (AU), puts it nicely: We want to be unique in some ways but also similar to others.

Social identity at work

At work, our social identity guides our behavior. It makes us more susceptible to ideas from similar others. Professor Naomi Ellemers (Leiden University, The Netherlands) explains that we use social identities "to make sense of complex social situations"[2]. Once a social identity is activated (i.e., your identification with a specific group influences your behaviors), we make the actions of the corresponding group and their achievements our own. We feel sad when our organization has lousy press coverage. We feel proud when others consider our profession crucial for humanity’s survival.

As I'm talking about social identity, it is necessary to address issues of power and privilege related to group membership. In "Your full self: Social identities and the workplace", social identity is linked to issues of power and privilege. Not every social identity has equal access to opportunities. Changing access to opportunities decreases the privilege of some. Of course, many people don't like this. The feeling of us vs. them increases, and people get more protective of their social group.

The danger with social identity is that people will go to great lengths to belong to their group. This effort is visible through behavior that can become harmful for them or those around them. As with anything, too much isn't good. This also applies to overcommitment to your profession or your team. In a way, you lose yourself in your group and become blind to inequalities or negative consequences.

Several years ago, I studied how social identity influences professional development and team performance. I asked 15 professors for their opinion. Below are some of the things they said

Identifying too much with your team can lead to

- You are doing whatever the team wants, disregarding personal needs, your ethical standards, and the values of your profession. One professor called it professional blindness; you forget the best practices of your domain.

- You are protecting with all means your team from any changes, even if they would be beneficial.

- You are considering all things created by other teams as sub-optimal.

Identifying too much with your profession can lead to

- You forget what the goal of the team is.

- You are neglecting the input from people with other backgrounds.

- You are avoiding any changes that threaten your current way of working (aka routines).

Without identifying with your profession and team, you’d be indifferent to success and work standards. A doctor who doesn't care about medical norms is likely to be costly. Don't overcommit to your team or your profession; you might drive yourself and your team off a cliff.

You have many different social identities. One for each group you identify with. Depending on the situation, one social identity will be dominant. This dominant social identity influences your behavior.

Keep in mind that your social identity exists only in your head. Your identification with a group is mental, and as a consequence of this, you will behave in such a way that others can see that you belong to that group. You are also "born" into other identities (e.g., your gender and ethnicity). Canwen Xu talks about this: Having one identity just because of the color of your skin. In her speech, she addresses how she dealt with being Chinese but growing up in a predominantly white neighborhood. In her case, she felt like she didn't belong and took action to feel more similar to her white friends. It raises the question of how your environment influences who you become or want to be.

Exercises & how-to

You need to identify to some degree with your profession and your team. But how much is enough and how much is too much? Below are a couple of exercises to help you think about this.

The idea is to determine if you are overcommitted to your work or team. To do this, you have to sit down and think (reflection) or go out and do stuff (experience). Of course, ideally, you do both, alternating between thinking and doing.

Why? To feel more secure about what your boundaries are.

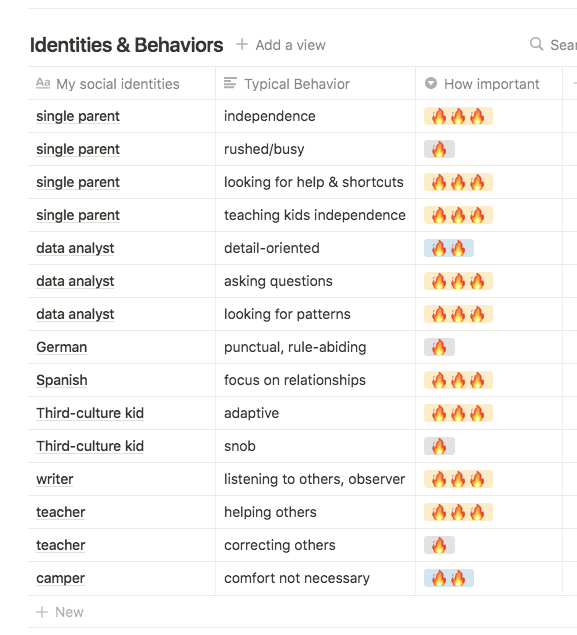

Think about who you are and what activities you like to do. That gives you a starting point. For example, this is my list of social identities: single parent, data analyst, German, Spanish, third-culture kid, scientist, alt-academic, female, writer, indie hacker, teacher, hiker, camper, sailor.

For each social identity list a couple of (typical) behaviors or norms. Then for each behavior or norm, indicate how important this behavior/norm is for you.

Why? To shape your work around your (work) values.

Write out your work values and what your team/company values. Think about how you communicate with team members, how professional development is organized, who is shaping the team's strategy etc. Then see how much overlap there is. If there are conflicting values (e.g., productivity/ hustle culture vs. family time; loyalty vs personal growth), what side will you pick?

Team version: To create a team everyone feels like they belong, you need to establish behavioral norms everyone agrees to. Turn this into a team exercise by asking everyone to answer the questions, and then discuss your results. Discussion can be synchronous or asynchronous.

Why? To figure out how much your identity is tied to your work.

If you get fired tomorrow, who are you? Can you detach your identity from what you are doing to pay your bills? A slightly different question would be "How much are you looking forward to retirement? What will you be doing and in what way will your day be different than they are right now?" The ethos is the same: If you are not working, can you tell me who you are?

Why: Become aware of which social group dominates the thinking and consequently decides what behavior is acceptable.

The original exercise, as described here asks you to see who, based on gender/ethnicity, etc, is most privileged. You can do the original exercise, or modify it. Replace a demographic variable with your departments.

Bibliography

- Ellemers, N. (2012). The group self. Science, 336(6083), 848–52. doi:10.1126/science.1220987

- Brewer, M. B. (1991). The Social self: On being the same and different at the same time. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 17(5), 475–482. doi:10.1177/0146167291175001